News From NEAM: July 2015 Edition

Accordions And Their Stories: A Living Legacy

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]The New England Accordion Museum opened its doors in the Fall of 2011 in Canaan, Connecticut. How it came to be is, in itself, an interesting story. I learned to play the accordion from age 10 to 17 while growing up on Long Island.

I was part of an accordion band and, as was the custom back then, participated in many competitions and contests. However I remember being one of the more reluctant players who did not like the stress of the competitions and the practice that was required to do well.

But I must admit, as I look back, the challenges I faced in learning how to play in front of an audience and disciplining myself to practice helped prepare me for my eventual career as a CPA.[/one_half] [one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]

[/one_half]

[one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]Fast forward some 42 years to 2008 when I woke up one morning with the inexplicable urge to start playing the accordion again. To this day I cannot figure out what caused me to suddenly desire to play again, but the process had begun.

[/one_half]

[one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]Fast forward some 42 years to 2008 when I woke up one morning with the inexplicable urge to start playing the accordion again. To this day I cannot figure out what caused me to suddenly desire to play again, but the process had begun.

I found an accordion collector that very same day in the middle of Vermont (of all places) where we were vacationing. He had about 125 accordions in his collection and I began looking for one that would suit my needs.

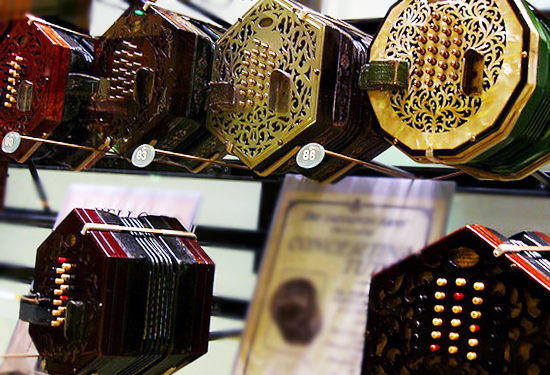

In the middle of the room, stacked on the floor and separated from all of the other accordions, was a pile of small concertinas, about 20 or so all together. They were brown, rusty and dirty looking. I asked about them, and the owner told me that he had just purchased them from a well-known collector.[/one_half]

These, he said, came from the Nazi prison camps of WW II. As I stood there looking at them, an eerie feeling came over me as it was the beginning of my reason for collecting accordions. I started to realize then that there was something very special and unique about the accordion.

Paul Ramunnni, Director of NEAM

Accordions Have a Legacy To Continue

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]It has participated in the development of our culture for approximately 200 years. It came across the prairies as the West was settled. It was portable and accompanied people wherever they went and they usually took it out to be played in happy times as well as trying times as during war, armed conflicts, and in God forsaken places like concentration camps.In a word, the accordion has become part of our Country’s DNA. It has a legacy to share, not only for America, but for many of the world’s cultures. That alone is reason enough for us to work hard at preserving that legacy as we move it forward into the 21st century. Our collection at NEAM has over 400 accordions some of which were involved in the major wars that have occurred in the last 200 years.[/one_half] [one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””] [/one_half][one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]

[/one_half][one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]

Accordions And The Memories They Created

We have a flutina that I purchased from a person who believes that it was owned by someone who was at Bull Run during the Civil war. It came in a very sturdy compact oak carrying box. Reportedly, the soldiers at that time would take an instrument such as this with them into battle and would play it at night as they sat around the campfire. It offered support and comfort to the troops as a reminder of home and better times.

But the instrument would often change hands and sides in the conflict if the owner was killed in battle, as surviving soldiers would find it and keep it. Not long ago, I received a donation of a small wooden button box from a friend in Great Britain. The accordion came from his friend’s family and was owned by someone who fought in the trenches of WWI.

The story goes that this person played for the troops while they waited for the order to attack or prepare to fend off an assault…The owner had to work the bellows after the gas attack while his mask was still on to get rid of any gas that had settled in the unit while on the ground. But it survived, as did the owner, and both were still in good working order after each attack.[/one_half]

Mustard gas was the weapon of choice in that war and whenever the alert came that there was an attack imminent, the soldiers would literally drop whatever was in their hands and rush to put on their gas masks. This small, brown and very plain looking accordion was dropped and gassed at least two dozen times.

Paul Ramunni, Director of NEAM

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]I remember the story being told to me of a Jewish boy Alex Rosner, the youngest child rescued by Oskar Schindler during the Holocaust. Before coming under Schindler’s protection, Alex was sent to Auschwitz and he had his accordion with him.

The Nazi guards kept him alive because Alex was forced to entertain them with his music. Schindler stayed in close touch with Alex and his parents throughout the remainder of his life. His accordion was a small Traviata and is on display at the Holocaust Museum on Long Island.

I have heard a number of these war time stories where people were kept alive just so they could play accordion music for their captors. The following three stories came to me via family members of the people who owned and played their accordions during WW II.[/one_half] [one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]

[/one_half]

[one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””] The first story was from a chief Navy mechanic on a USS aircraft carrier. His job was to keep the planes mechanically running when they returned damaged from missions. Tom played an accordion and had it on board with him. Interestingly, his shop and crew were in a very large cavernous area below the main upper flight deck.

The crippled aircraft would be lowered by elevator down to his secondary deck to be worked on. But sometimes at night when things were quiet, he would play his accordion in that lower deck area. The acoustics were amazing. The sound of his playing would permeate the entire ship.

Tom soon realized that his playing was probably the last time some of the fliers would ever hear music that reminded them of home. He played for them… it was his way of encouraging them.

[/one_half][one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]The next story is about Walter, a tank driver for General Patton’s 10th armored division. Walter played an accordion but didn’t have one as his unit moved into Germany in the latter stages of the war.

They were shelling a German town when a building took a hit on its main side wall. The wall collapsed and exposed a desk with a full sized Hohner piano accordion sitting on top of it.

Walter stopped the tank and ran through the firefight to get the accordion. He managed to get it into the tank and later played it for the troops whenever they stopped for rest. His family sent me a “souvenir” that Walter picked up for his meritorious service.

He was hit with fragments of a shell fired from a German “88” howitzer. The surgeons took the shrapnel out of Walter and gave it to him. He did receive a purple heart for it too.[/one_half] [one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]

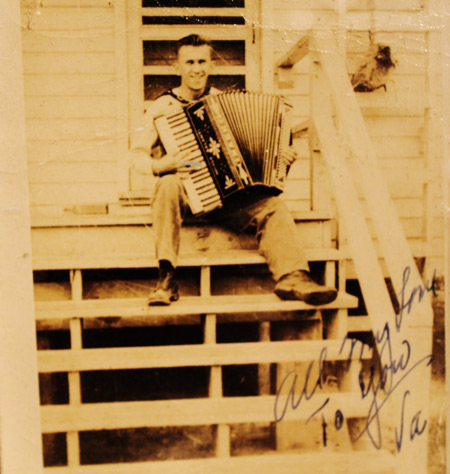

[/one_half] [one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””]This last story is about a young girl named Barbara O’Connell. I believe she grew up in the middle of the USA and learned how to play the accordion as a youngster. From all accounts, she was a stellar player. Around 1935, she asked her Dad if he would buy her a professional accordion. Now, her father made something like $20 a week in those days.

Even though the Great Depression was in full swing, he agreed to order her the accordion. It was a full size special order Chiusaroli made in Castlefidardo, Italy. It cost $750. For that amount of money, in those days, a person could have bought a small house or certainly one of the best cars on the road. So, the whole family went to work to raise the money.[/one_half]

[one_half last=”no” class=”” id=””]

After WW II broke out, Barbara announced to her family that she wanted to join the USO and travel to Europe to entertain the troops. She was only 19 years old at the time. And she did just that. She entertained well over 200,000 troops while on tour. She learned, like Tom the Navy mechanic, that her accordion was her second voice.

She could speak to people while playing music….the accordion translated her sentiments into a special language. She had to memorize all kinds of songs to play for not only American soldiers but for troops from our allies coming from other countries. Oftentimes she would choose “God Bless America” as her last song. It was her way of sending them off encouraged and blessed.[/one_half] [one_half last=”yes” class=”” id=””] [/one_half]